NE’S UNDERGROUND ORIGINS WITH MAN POWER

Man Power speaks with the same passion about composing a symphony for the Royal Northern Sinfonia as he does about pulling Paul Woolford out to North Shields Social Club for a 5 hour marathon of b2b balearic-psychedelica. If you think these are at odds, he says your music ecosystem’s failing you. After exhibiting the Man Power project at Panorama Bar, Fabric, Circo Loco and their counterparts the world over, it was to the shipbuilding sites of Wallsend that he returned - with a voice memo app at the ready.

Over an Irn-Bru in Ernest with Lucy, he lifted the veil on his early experiences of Newcastle’s electronic scene and they discussed how to ensure it prevails.

LA: It feels like a sort of renaissance is happening in the North East right now and isn’t being documented. I want to know about our legacy and history. How has the scene evolved?

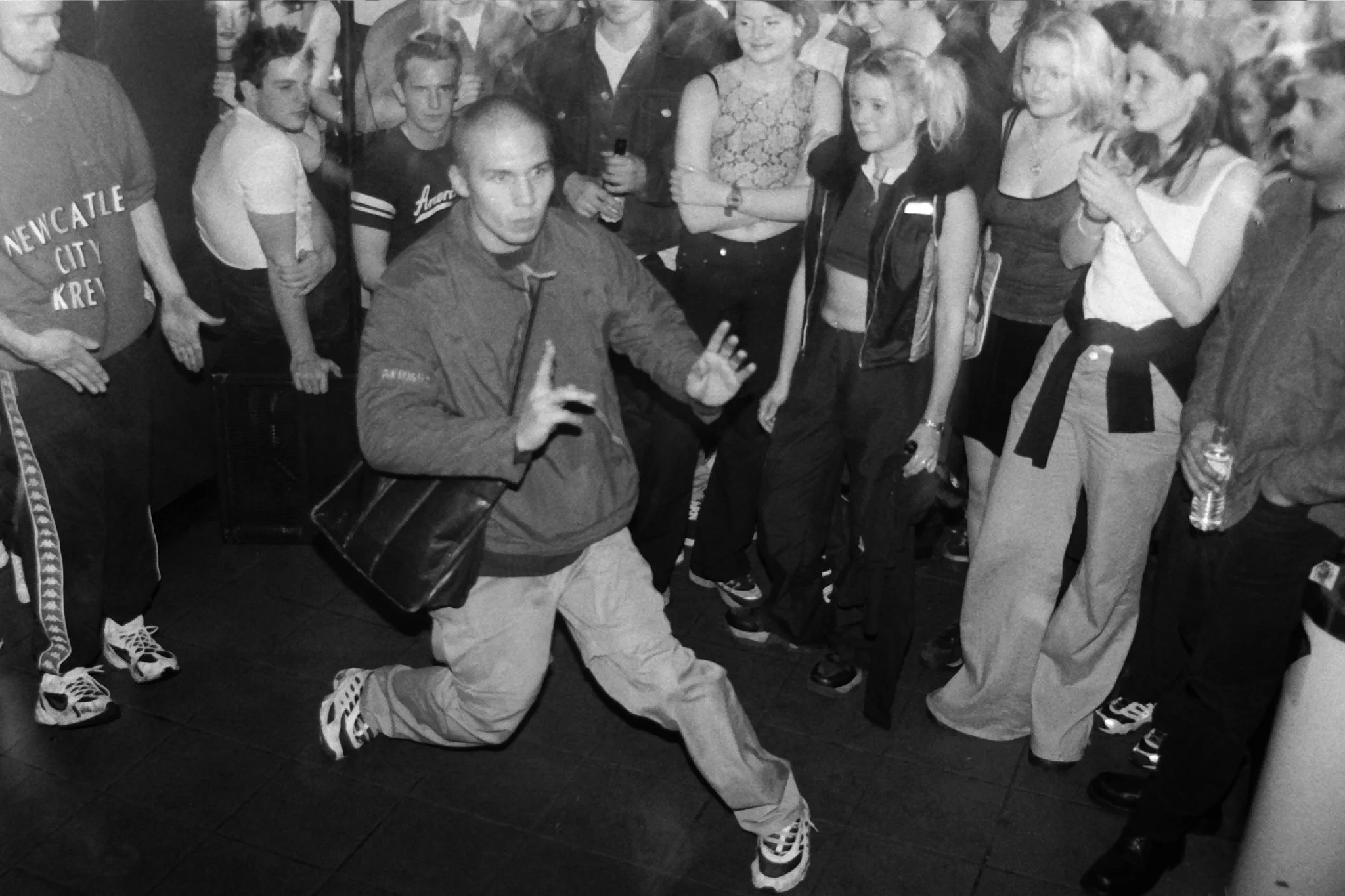

MP: Dance music is really important to our regional identity and certainly our arts scene. I first really got into it at Shindig, at the Riverside, where Oasis played in Newcastle for the first time. It was an indie and live music club and on Saturdays they gave it over to house, for Shindig. Shindig first started off where World Headquarters was originally — when it used to be called Club Africa — but it came alive over at Riverside, which later became Foundation. The fact that people in the region were playing house music that regularly from such an early time, every single week, was really something. There were a lot of bands and people thinking they were rock and roll. Lots of post punk vibes. Then this new thing that had been getting big for a few years - house - seems to have taken over. A lot of this is before my time but the North East’s parties were huge. Including County Durham too, it did have a big foothold in the region through clubs, free parties and outdoor raves.

LA: Where do you see yourself against that landscape?

MP: I was thinking about this on my run this morning. If you think about 1988 as like, year one; obviously there was stuff going on before that but that was when people were coming back from Ibiza and brought it back here; I reckon the first wave would be folks who were 18 five years either side of 1988. I was only 8 in 1988. I was 18 in 1998 — the third wave, if you like, of people getting into the scene. And I don't know too many of the first generation but a lot of my best friends are from the second. My generation was kids who were a little too young when it first came out but grew up on it. Young enough to exchange tapes at school and old enough soon after to start going and participating. It was definitely the big thing here back then, but nothing was very much written about the North at the time.

LA: I mean, we’re back there now.

MP: Very much so, I agree with that. My dad had a theory; the more I think about it the more I think it’s true. If you look at the industrial history of the North East vs the North West you have Manchester — cotton industry and warehousing — so you have to deal with people from Leeds or these market towns, you definitely see a lot of people. Liverpool it was docking, where again you’re dealing with people coming and going. Leeds was markets. Newcastle was shipbuilding and coal mining. We made things or pulled them out of the ground and people took them and fucked off with minimal contact with our communities. It developed this regional, working class attitude of self-sufficiency; for a very long time it’s been this feeling where things happening in this region are happening to people in this region and we’ve not seen any need to project it out there.

LA: And in turn you could argue that’s produced a distinctive sound.

MP: Well it has. I will always maintain that the best DJ’s I ever heard coming up — and I don’t mean to sound like a wanker but I’ve been everywhere — I still think the best DJ’s are I’ve ever to hear coming through were over here, and were the people from the North East of England. It was this very specific approach to balearia, it’s a very schooled sound, it’s a bit techno it’s a bit house but it’s also very post-punk and it’s got this real balearic spirit. In the oldest definition of the term when it applied to people like Leo Mas at Amnesia, one second you’d be listening to a Cure record then it would be the Wooden Tops then it would be some really heavy electro or some EBM - the well worn phrase is that it’s a feeling rather than a genre. I guess the term balearic is of those things that when you think you know who it’s referencing it means you’ve probably got it wrong, you get what I mean? Over years the term seems to now just mean slow house music with guitars, and that’s a bit boring, a reduction of the term, but I was brought through with balearic meaning an anything-goes attitude to selecting music, which I think is a real cornerstone of the British sound.

LA: How did you come to be deep in the scene?

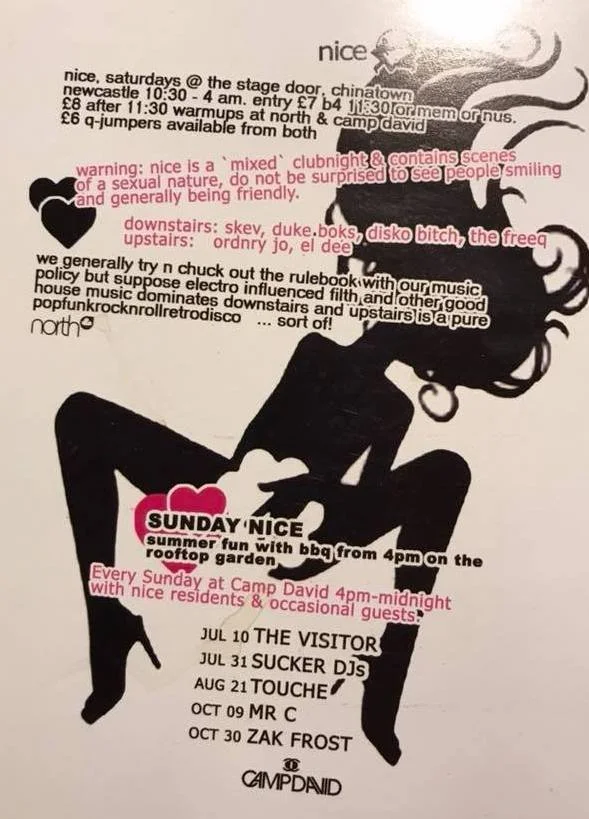

MP: It was around 2003, and the music that was coming out was like super middle of the road proggy stuff, you know sort of white guys making the same generic stuff and it wasn't very sexy or very punk or very jazzy, just very straight up. I started creeping back in to the scene through things like electroclash and DFA Records stuff which we used to call punk-funk, and then I started DJing just a lot more varied stuff — hip hop, funk, TV Themes and whatever else, we’d just play anything — at this club called Nice which was the alternative to Shindig. I became a resident there, I was upstairs and I guess I just started bringing in more and more things that would have worked in the downstairs room instead, and I ended up moving into playing that more house and techno-leaning room.

LA: Do you miss it?

MP: It feels like a period that just doesn’t really exist anymore because you struggle to get people of all descriptions into a room like, for group therapy; just to dance to anything as long as it’s cool as fuck. Now with all these pockets of the internet, there’s this whole dictionary of terms so big it loses some of its expression.

LA: Using more complex genres to position themselves away from the mainstream.

MP: There is that. But the mainstream is something that touches everybody now, and the underground subculture idea has been co-opted, so like to reject the mainstream you also have to reject the mainstream underground. You can’t just do something alternative, you have to do the most alternative thing and like, are you actually doing anything? On one side you’ve got things that exist purely for expression and on the other you’re trying to appeal to whatever cult mentality is dominating. And the trick is, somewhere in the middle, to hear something worthwhile. I got on a trajectory, hoping that people would connect with what I was into — I achieved that in the first two years. Then I’m on a stage at Glastonbury and I had a two year period where I was just like: what’s the next step, what’s the next way to get bigger? I got to the point just before the pandemic where I was like, ‘this is shit, I'm chasing a whole load of things that I'm not actually that into.’ When the pandemic hit I was actually okay in that sense as I just thought I already didn’t like the things I was getting. It’s very easy to fall onto the hamster wheel of doing something for it to be self-perpetuating rather than because you enjoy it.

LA: What is it that you enjoy? Or more like, which stuff makes you feel most connected with your creativity, to produce? I know that you came back here and recorded these local everyday sounds for the Bed Wetter album.

MP: Yeah exactly, all of that stuff. I found archive recordings of the shipyards and I went and geeked out doing things like getting field recordings of the Metro, I even managed to find online archive recordings of family members talking about life almost 100 years ago, and incorporated things like T Dan Smith talking about development of Newcastle, a lot of things that seem to sum up my emotional impression of the region over the years I’ve been alive — it went great. And then Sage Gateshead got in touch saying they wanted an artist in residence so I went, I'll have a go, and there’s a lot of Japanese companies that come and make a base here, like Nissan and I wanted to incorporate that. I figured I’d see what a working class person from Battle Hill has in common with a working class person from Komatsu City and vice versa, so I gave them that as a rough outline and they loved it. I went, I’ll do it with an orchestra then and they were fine and it’s like, come on — so I kept on coming up with more outlandish ideas. It felt like a working class heritage thing and I knew from the off that I wanted to do it in a way that hopefully helped other people who come from a place like me where they felt that art wasn’t something they were supposed to take part in.

LA: Art can feel like it’s too precarious financially, you’ve not got the space to fail.

MP: Exactly, there’s this necessary-for-survival thing ingrained here, like if you want to draw pictures in your own time that’s fair enough, but. Being a North Easterner is perhaps a little bit challenging to you succeeding. You can do it if you’re in London, you can do it if you’re in Berlin, you could do it in the States but if you stay here you feel like no one‘s going to write about you, no one’s going to talk about you, no one’s going to want to know what you do. Left unchecked nearly every bit of fucking talent can develop this feeling like if they stay in this region, they’ll be buried. We cannot leave it so that the neglect from these big media organisations have our DJs, or any creative people, thinking that staying in this region will be an obstacle to success. That will either impoverish peoples’ ambitions, or impoverish the region by seeing its talent move elsewhere.

LA: It was so appreciated when you tweeted at Boiler Room to sort it out.

MP: I just think there’s a duty to be a bit more vocal about it. If you use us to run a ticketed event here at a venue where you don’t platform those artists to the fullest of your platform’s ability, then you’re just rinsing the region, taking money out of the hands of local promoters, and brushing us under the carpet.

LA: I know you’ve spoken a lot about how austerity stripped the arts scene, more here than anywhere. A lot of people coming through don’t know what it looked like before those cuts. If we’re going to stop being dependent on outside names for validation, how can we provide that infrastructure to flourish by ourselves?

MP: I think that’s a very valid question and my warning would be not to get caught up in recreating what’s been done before. Determine what you want it to look like and what you want it to do. From the austerity side of things you’ve got to go: what is it, can you remove it, or how can we neutralise its effect. The big one here is the general level of poverty, essentially. So what does that mean for us? How do we get youths in the best position to have more access to the pipeline and their hands in a deeper pocket? This place is so fertile but the safety net for people to try and do interesting things isn’t there. Another one is creating community spaces. Cobalt is a great example of that. World Headquarters too and their investment in community projects. From that, more things will come. Even if it only lasts for a few years, it’s evolutionary. Our party in North Shields fulfills a community purpose: the crowd’s different from your normal city centre only-young-people crowd, there’s a broader range of different people there for different experiences. Trying to connect these disparate threads - that’s what’s actually needed, and more and more things are against that community ideal now as everything’s commodified. There needs to be more support for that kind of energy.

LA: Parties here really welcome big artists as collaborators instead of headliners; I think that helps.

MP: It makes perfect sense. This headlinification of artists over the last 15 years is detrimental for everything, it’s really distasteful. I’d much rather have ten 300-capacity events than one three thousand, with them all representing something else. And there’s no reason why that shouldn’t be the case. Business people know they can make millions packing out a stadium and reduce the amount of people who share that amount. The only people who really make money are the management, the venue owners, and the artist and everybody else is frozen out. There’s a space for that consumption and it should exist. But there should be more people rejecting it and doing things that are more varied and see a more equitable distribution of the proceeds.

LA: What role do you think social media plays here?

MP: It's not good for crowd diversity at all, the way you’re directed to ‘your’ events. In Newcastle it really shows in the polarisation between student and local events. If there’s anything that I think could benefit the region now, it’s working with each other, going to each others’ parties and introducing each other to new things more widely. Posters and flyers are a good way around it too - when everything’s digitised there’s something that goes so deep about standing on the street putting flyers in someone’s hand. The hit rate would be very low but it’d be entirely worth it via that human connection and by reaching new groups of people, whether for further dissemination or for them to take part directly.

Wallsend’s Finest is out now on Bandcamp. Get your tickets quick for Man Power’s next party and keep up with his movements on Instagram.